Mining Memories

The dwindling few who recall living

in Bingham Canyon fight to keep alive memories of a community that was stolen

from them.

by

Stephen Dark June 29, 2016

|

| Waste-Dump car with Brakeman |

This man-made mountain is far more

than a dumping ground for the byproduct of a 113-year-old open pit mine that is

one of the largest in the world. It's an unmarked tombstone, a resting place

for the hopes and dreams, the lives and loves of a community once known as

Bingham Canyon.

At its peak, Bingham Canyon was home to more than 15,000 miners and their families who had come from all over the world to work the mine. The community's main artery was a 5-mile, 20-foot-wide Main Street that snaked up the canyon. At the Bingham Mercantile store at Carrfork, the street split. To the left was a one-way tunnel that led to the hamlets of Copperfield and Dinkeyville and to the right led to Highland Boy. "That canyon was so narrow, a dog had to wag its tail up and down," old-timers quip. Throughout the canyon were small communities bearing such now-politically incorrect names as Frog Town, Jap Camp and Greek Camp, each reflecting, to some degree, its residents' ethnic make-up.

|

| Copperfield to Telegraph |

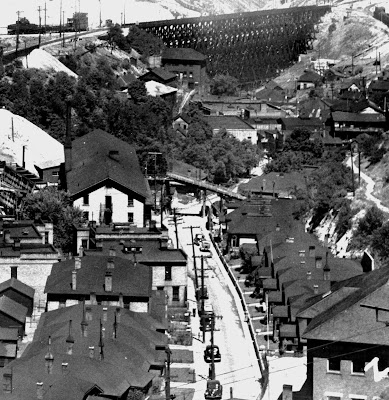

1.jpg Main Street, looking up to

Highland Boy, looking down Carr Fork

"Our confinement between these

towering mountains seems to produce a closer bond of fellowship among the

people," wrote Mayor Ed W. Johnson in the 1939 souvenir program for Galena

Days, the first of a series of frequently held celebrations of mining and

canyon life that continued until 1957.

With Salt Lake City 30 miles away,

Bingham had every amenity you could want, be it neighborhood grocery stores,

cafés and bars like Pasttime and Copper King, and even its own movie theater.

Local, retired advertising executive Bill Nicholls lived in Frog Town as a

child, and remembers paying 45 cents at the Princess Theater to watch Flash

Gordon serials, eat popcorn and drink malted milk.

Compared to the long-dominant Utah

migration narrative of persecuted white Mormon pioneers pulling handcarts to

what would become Salt Lake City, Bingham's all-but-

marginalized story was of a wealth of international migrants from the late 1800s onward, who ultimately would be driven out by the very mining companies that paid for them to come here.

marginalized story was of a wealth of international migrants from the late 1800s onward, who ultimately would be driven out by the very mining companies that paid for them to come here.

For all Bingham's picturesque

small-town pleasures, life was hard for both miners and their families.

"Women who married three times, still outlived their husbands,"

Kennecott retiree Eugene Halverson recalls. He estimates between 300 and 400

miners died each year from lung diseases related to inhaling mine dust. Dust

wasn't the only killer—accidents, cave-ins, along with avalanches and fires

jumping shacks so close you could hear your neighbor snore—made life in Bingham

hazardous. But the people who lived in the canyon, and in Lark, a smaller

mining community directly to the east of the mine, loved their communities with

a fierce pride.

|

| Bingham Days |

Since the late 1990s, the

foundations of Bingham City have been buried beneath a mound of waste rock so

high it all but eclipses the snow-capped mountains behind it. Lark, meanwhile,

is a wasteland.

Halverson

has for years written about his memories of Bingham life on a blog called

"Gene's Family Tree." In a post titled,

"Bingham,

a time to cry," he quotes a deceased former

mine worker. "Yes, I envy all of you that can go back to your home town

and sharpen memories of day gone by, because I have only my memories to reflect

on. The town I spent my youth in is gone. There is no remnant of the town to

sharpen my mind—nothing to focus on and bring in to sharper remembrance those

long-gone days."

|

| Telegraph in winter |

In the last few years, Bingham and

Lark's former residents have brought their long-buried yet still mourned homes

back to life, freeze-framing and sharing their memories through virtual communities.

Bingham native and now St George resident Eldon Bray administers a Facebook

page called "Bingham Canyon History." Some of its 1,946 members post

photographs of Bingham, its streets, businesses, people and craggy landscape. A

community that had vanished from Utah is viscerally evoked in black and white

images as those who lived in Bingham and their relatives post joyful comments,

having identified faces and places in the pictures

previously consigned only to fading memories. On a Facebook page entitled "Lark, Utah," along with historical images of the town and its people, amateur historian and former Lark resident Steven Richardson has provided a wealth of documents, news clippings and reminiscences about the town's history. As one woman writes on the Lark page, beneath a 1947 school class picture, "I love to see pictures like that. It makes my heart happy."

previously consigned only to fading memories. On a Facebook page entitled "Lark, Utah," along with historical images of the town and its people, amateur historian and former Lark resident Steven Richardson has provided a wealth of documents, news clippings and reminiscences about the town's history. As one woman writes on the Lark page, beneath a 1947 school class picture, "I love to see pictures like that. It makes my heart happy."

KEEPING

STORIES ALIVE

Mining is a brutal industry that

devastates landscapes. The obliterated Oquirrh Mountains speak to that. The

company gets its ore, workers get their salaries and one day the community has

to pick up the social and environmental pieces left behind.

The corporate-driven demise of

these two communities, protracted over years as far as Bingham Canyon was

concerned, a few tension-filled months in Lark's case, left only those who had

lived there to mourn their passing.

"They

took my memories," Halverson says. "They buried

Bingham. I used to be able to go to the top of the mine and see where things

were." With no trespassing signs keeping people away, "Now, I can't

even go up there. Just seems like they took everything away from me."

"You

miss out on so much companionship and love and feelings," says Stella

Saltas, the 88-year-old mother of City

Weekly publisher, John Saltas. She was born in Bingham and had to join the

forced exodus from the canyon in the early 1990s. Since then, she has lived in

a rambler in West Jordan. The long-gone city, she says, "will always be

home. I live here, but it's not home."

Many of Bingham's displaced

citizens say they left a part of themselves in the canyon that they never

regained. Some, such as authors Eldon Bray and Scott Crump,

have self-published books celebrating and preserving their memories of the

canyons.

Other former residents meet monthly

at cafés and restaurants to share memories and keep alive old friendships

forged in Bingham. Then there's the Fourth of July chuck-wagon

breakfast at Copperton Park, a tradition

started in Bingham Canyon and continued in Copperton by the local Lions Club

chapter.

|

| Ada Duhigg |

London-based mining conglomerate

Rio Tinto purchased the mine in 1989. On its website, it employs similar tools,

but instead of an adhoc tour of personal histories and recollections, the

corporation favors a 360-degree panoramic tour of the mine, which measures

three-quarters of a mile deep by two-and-three-quarters miles across. "You

can see it from the moon!" the tour guide in the video says.

"Currently, we are planning on

operating until at least 2029, and the long-term outlook for copper is

strong," spokesman Kyle Bennett writes in a response to emailed questions.

Meanwhile, far from its shadows, in

kitchens and basement studies, the children of Bingham Canyon build through

photographs and words a virtual re-creation of a beloved world long since lost.

Halverson

says they have no choice. "If you don't write these stories, and don't

pass them on, they will die."

MAKING

YOUR MARK WITH YOUR FISTS

|

| Erma's mother Highland Boy |

Individual mining claims gave way

to acquisitive businesses. By the early 1950s, U.S. Smelting, Refining &

Mining Co. owned the underground mines that let out near Lark, and Kennecott

Copper owned the above-ground mine directly to the south of Bingham Canyon.

Johnny

Susaeta is a spry, twinkling-eyed 93-year-old

who still displays the rugged good looks captured in photographs of the heroic

local football star 70-plus years ago enshrined in a room dedicated to alumni

at Bingham High in South Jordan. The World War II veteran and retired Kennecott

worker's parents were Basques who met in San Francisco after emmigrating from

Spain. Susaeta grew up in Highland Boy, where he knew Slavs, Italians, Serbs

and Croatians. "I spoke most of their languages when I was young," he

says.

It was a tough town to grow up in,

one where fighting was a way of life. "I got in a fair amount of

fisticuffs," Nicholls recalls. "Fighting was your

way into making your mark and being accepted."

While Bingham taught its residents that diversity and acceptance went hand-in-hand, when they went to Salt Lake City, they'd often experience rejection. "When I went to the valley with my Mexican friends, they wouldn't let us go dancing unless I ditched them," Halverson says. "Well, hell, who would want to ditch their friends?"

When hostilities broke out in

Europe at the beginning of World War II, Bingham ethnicities of every stripe

went to war, leaving women to take over mining work. "Everybody in town

was signing up," Halverson recalls. Johnny Susaeta signed up with four

friends. "We ran around together, so we decided we'd go win the war." Three made it back uninjured.

Nicholls' father was a blacksmith.

At war's end, he bought the Coppergate bar in Bingham. Wide-eyed, 8-year-old

Nicholls arrived in Bingham just days before the end of the conflict. Each

night, he went to sleep to music from a jukebox in the bar below playing

country music. The day the war ended, he marveled at the parties in the street,

people hanging out windows banging pots and pans, firecrackers going off as

residents sang and danced in the streets.

Meanwhile, next to the mountains, Lark

had a store, a gas station and a hotel, a bar and two churches—Catholic and

Mormon. The land itself was owned by the

U.S. Smelting, Refining & Mining Co.—some residents owned their homes,

while many took advantage of cheap rents, the mining company-cum-landlord

preferring to subsidize rents to have its employees close by.

Lark sat on a hillside with

spectacular views of Salt Lake Valley. "It was right on the corner of the

valley," says Lark historian and former Kennecott geologist Richardson.

"You could look out and see the Wasatch Mountains." He and his wife

would go for walks after dinner on the sand dunes, the smells of the copper

minerals in the tailings that formed the dunes rising up to greet them.

What it shared with Bingham was the

same miners' work ethic, and for some the same net result, men dying young of

silicosis and their widows struggling to support their children.

Unless you owned your home, renting

from the company made you vulnerable to eviction, if, as in the case of Crump's

grandfather, you fell sick with "miner's

lung." He and his family were evicted because he couldn't work anymore.

A friend found him rooms elsewhere in Lark, where his wife cared for him until

he died. She raised her children on a tiny pension until she found work at the

Lark Mercantile and as custodian of the local Mormon ward house.

With the world's insatiable appetite

for copper ore, the various canyon communities the mining corporations had

relied on for labor found themselves in the way of the mine's expansion.

The process of families being

displaced that first began with open-pit mining operations, picked up pace in

the 1950s. By 1959, Kennecott Copper began aggressively buying up canyon

private properties and homes. At a meeting, Dunn quotes one resident saying, "Why

should we sell our homes for a song, move to the valley and go into debt 20

years?"

"It was all ending,"

Nicholls says. "Almost all of them were gone, there were a few holdouts

who didn't want to take their pennies on the dollar offer."

Nicholls' father sold his

Coppergate bar in 1961. The work had taken its toll on him, his son

says."It just about destroyed him physically. He was an alcoholic, it was

hard, hard work. He went through years of real struggle financially to keep

things going."

Kennecott offered to pay the

appraised property market value. Nicholls' father paid $39,000 in 1945 when he

bought the bar. Kennecott offered him the same amount to sell in 1961. While

his father wasn't pleased with the offer, "he was just happy to get out

and get out with something," Nicholls says. "They

really had the city over a barrel."

THE

BATTLE FOR LARK

Compared to the campaign of

economic and social attrition Kennecott waged successfully against Bingham

Canyon, the mine's owners faced a public-relations nightmare when it sought to

raze the much smaller town of Lark.

On Dec. 14, 1977, a Kennecott

official summoned Lark's 591 residents to a meeting at the LDS ward house. It

had just agreed with UV Industries, which had previously bought out the U.S.

Smelting, Mining & Refinery Co., to pay $2 million for 640 acres, which

included Lark. The people of Lark had to vacate their homes by Aug. 31, 1978.

Those who owned homes had to move them; those that rented faced eviction.

Kennecott would neither buy the homes nor pay moving expenses, the official

said. The company, he added, "is not in the housing business."

The acquisition, Rio Tinto's

Bennett says, was for several reasons, including "owning buffer property

adjacent to (the mine) and as a site for infrastructure that captures and moves

storm water."

|

| LARK |

Hilda Grabner was a descendent of Cornish miners, who were among the first immigrants to start mining the canyon. The retired teacher had lived in Lark on her own since her husband died in 1939, cultivating an immaculate English garden.

Then 81-year-old Grabner was one of

six Lark residents who, strangers all to air travel, nevertheless flew to New

York to attend a stockholders' meeting of the financially struggling Kennecott.

Grabner and another resident were given five minutes. One irate shareholder

shrilly interrupted them multiple times with the question, "Are they

stockholders?" Grabner silenced her by replying, "We're

stockholders in human lives."

Faced by a swarm of reporters

reveling in the David-and-Goliath fight, Kennecott extended an olive branch. In

early May 1978, it offered 120 percent of the appraised value of the homes,

$1,000 toward the cost of relocating, and moving owned homes to Copperton free

of charge.

Most of Lark's residents voted to

take the deal. Perhaps the final insult to Lark's memory was that the nine

white-board houses that were moved free of charge by Kennecott to Copperton,

were then clad in red brick as part of Copperton Circle.

Richardson

expresses frustration that he can no longer visit the land where his former

home stood and where he and his wife raised four children.

The last time they could walk there, they found pieces of a jigsaw puzzle his

wife had made in the dirt. There was the tree where his kids had played on a

swing.

"You can't leave the

highway," he says, as any straying on to where Lark stood is barred by

no-trespassing signs. "There's no sign there was ever a town there."

FRIDAY

NIGHT LIGHTS

Rio Tinto began dumping waste over

the former city and Main Street in 1997. Retired Kennecott employee Gary Curtis

recalls driving one of the first haul trucks to start the down-canyon dumping

on his mother's birthday. "I don't know I really realized the ramifications

of it," he says now. "You can't take away people's memories, but you

dump that rock in there, you've buried history,

I guess."

|

| MILLS |

By then, the last holdouts in Lead

Mine, which stood at the bottom of the canyon, had gone. Stella Saltas lived

there in her final Bingham years, the location of her

home and her father's precious garden still partially visible from the road

through a chain-link fence. "Little by little, they did it, till you're

about the only one left," she recalls.

5.jpg Lark

"I wanted to stay there, that

was home, I loved it," she says. Her feelings for Bingham, wrapped up in

memories of daily coffee with her own mother on the latter's porch as hawks and

eagles wheeled in the sky, are "something you can't explain."

|

| Bingham High School |

"Bingham people came from all

over the world, really, to be miners," Crump says.

"They came from so many places speaking different languages and the school

was the gathering place, where they would all come

together, to first get ahead in America by getting an education. This was their

gateway to a better life, to learn English."

Rio Tinto ordered it razed in 2002.

Bennett says the building post-closure by the school district, "fell into

disrepair due to vandalism and became a safety hazard," so they had it

torn down.

Fourteen years on, feelings still

run high. "It's just a sin it was leveled," says Nicholls.

While other residents grabbed small

mementos from the site, Johnny Susaeta and his three sons carried away a

2-by-4-foot, 200-pound capstone from one of the Art Deco school's towers.

"Everybody else took bricks," Susaeta says, standing by the capstone,

which they dug a hole for in his driveway. "We took that."

Now it's simply a weed patch. The

only sign there was ever a school there is some steps rising to where the

ballpark once stood that rang to the cheers of Bingham fans.

The Bingham Canyon History Facebook

page's membership, Eldon Bray

says, is largely made up of, "the children, grandchildren and

great-grandchildren of people who grew up in Bingham or worked the mine. The

town and the mine were all locked together in so many ways."

Sit with retired mine worker Gary

Curtis as he reviews old mining photos

online and the pleasure they provide are clear. He points to a picture of

Marvin "Rosie" Ray, father of Russell Ray, Copperton's former

postmaster, and recalls the time Rosie "chewed my butt," after he was

caught up in a fight. "There's Dr. Richards,"

he says, pointing to a 1930s photo of a barbecue. "He birthed me."

Thanks to Lark historian

Richardson's diligent efforts, including interviewing former residents and

posting their stories on Facebook, the Lark Facebook page paints a picture of

both the community and its demise.

|

| Bingham Kids |

Merritt coordinates the antiquities

section for the Utah Division of State History and as a deputy state historical

preservation officer, reviews "state and federal undertakings for their

effects on archeological resources." He first heard of Lark after a state

agency sent him a water-mitigation project Rio Tinto Kennecott was proposing on

the old Lark site. Merritt learned that while most of the buildings were long

gone, "the street system was still intact" in the surface dirt, and

there were several 1950s brick structures, along with the old water tower.

|

| Frog Town Kids |

Since the site is not publicly

accessible, working on documents he found in the state archives such as the

town survey, "led us to a digital preservation of the community. That

underscored you don't need to have that physical place to retain a community.

You can still have it through this digital expression."

Merritt plans to invite Lark

old-timers to the Sept. 30 Utah State History Conference in West Valley to

record their recollections of "what they remember about Lark, what sticks

out about it."

BARBARIANS

AT THE CANYON GATE

The sleepy town of Copperton all

but stands guard on Bingham's mountain-tombstone, dump trucks visible on the

waste-rock pile's upper echelons in the distance above houses on the west side

of Copperton park.

Once it had a café, a gas station,

a grocery store, an elementary and a high school, but "that's all gone

now," says Copperton resident Ron Patrick. "Basically it's like we've

moved away from some of the conveniences of the world."

Walk the quiet, drowsy streets and

you encounter few cars or people. Copperton has three churches, a Mormon ward

house, a Catholic and a Methodist church. Crump says being LDS and a

Republican, "I'm in a minority. Republicans met in a telephone booth,

while Democrats

were a force to be reckoned with. They met in the

Lions Club."

Walk with Patrick the block from his

house to his father's, and he talks about people he knows and the houses they

live in. He doesn't know the number of their house, just where it is. "People change," Patrick says.

"The town don't."

While residents talk about the

possibility of Rio Tinto one day buying out Copperton and leveling that, too,

Bennett writes that, "The Company has no plans to buy land within

Copperton in the future, and it is unlikely that land in Copperton would be

needed to accommodate growth."

That isn't true for Lark, though.

Tearing out the guts of a mountain, in order to process the less-than-1-percent

of copper ore it contains, generates 50 million tons of waste rock every year.

Rio Tinto is placing some of that waste rock close to where Lark stood, 40

years after it tore the town down.

The only threat, resident and

Copperton council member Kathleen Bailey sees, is encroachment from the valley

itself. "Every year, they build further up Bingham Highway. I think one

day they will be at our door."

Every Fourth of July morning,

Copperton Park rings to the preparation of a chuck-wagon breakfast and

the shouted encouragement of the young and the old as they take part in

three-legged races and other short sprints. "A lot of people from Bingham

come back for that day," Patrick says. "They'll sit here all day in

the park and just visit."

Where once the breakfast used to be

for 2,000 people, Patrick's father Bud says, "now you do good if you have

500 or 600. You don't get many people who lived in the canyon and remember

it."

This year's celebration will also

see the unveiling of a memorial to the demolished Bingham High by Salt Lake

County Mayor Ben McAdams.

Ask Rio Tinto what should be done

to memorialize Bingham Canyon, given the role it played in the mine's

development—including so many deaths from miner's lung—and Bennett responds by

highlighting his company's focus on achieving a "zero-harm

workplace." He writes, "We recognize the ultimate sacrifice many

miners made before modern health and safety standards were in place."

|

| Bingham High School Memorial |

In the late afternoon May sun,

Nicholls and Berg, Susaeta, a volunteer and a City Weekly reporter gathered

around the capstone. "This is the

key to our monument," Nicholls says. "We thought none of these

existed. When I saw it, I just about fainted." Berg squatted down by the capstone and dug a

little of the dark, loamy soil that had been its home for so long. "I call

it providence," he says.

The four men removed the capstone

and took it to a shed at Copperton Park, to join several hundred bricks and

smaller pieces of the old school's masonry that had been rescued by onlookers.

|

| Lark Days |