Translation of Ur historiens tocken from Klippiga Bergen (Swedish)

by NormanWesterberg Dec 2002

In the spring of 1861 a long caravan of wagons rolls along what is called the Oregon Trail. The caravan of about 60 wagons and 300 people is headed towards the “golden land” of California.

Members of the group entertain themselves by using native Indians that showed up along the way for target practice. They actually killed many of them. Perhaps it was the size of the wagon train and the large number of armed men that made the Whites do these insane tricks. The Indians choose not to immediately fight with the numerous pale-faces, but sent warnings to other tribes along the route. When the caravan has passed north of Salt Lake and arrived in southern Idaho, Indians from many tribes have already gathered to take vengeance on the murdering whites.

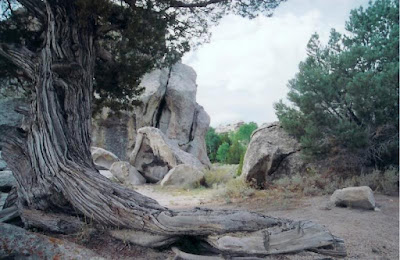

Early one morning the Indians attack at a place called Almo Creek near the “City of Rocks” mountains. The caravan leaders quickly order the formation of a defense circle. The Indians encircle the caravan, beginning a lengthy siege with sporadic attacks. The Indians do not have as modern weapons as the Whites, but there are many more of them, and they can exchange their fighters at the place of the siege.

The situation inside the White camp starts to get desperate. Water is soon gone, and an attempt to dig a well fails. During the nights several Whites try to get out to find water, but they are caught, killed and scalped by Indians. On the third day, due to the lack of water, the Whites start releasing their animals, which fall right in the hands of the Indians.

During the fourth night, five adults and a baby succeed in escaping from the camp. It is two groups that manage to get by the Indian guards undetected, one consisting of a young women and a young man, the other of a man, two women and the baby. One of the women carries the baby in a bundle by her mouth during part of the flight. The young couple manages to reach the Mormon settlement in Brigham, Utah, after considerable hardship. A rescue expedition sent from Brigham found the other three escapees barely alive, but the baby had died. When the expedition reached Almo Creek, it found all three hundred Whites – men, women and children, massacred by the Indians. The corpses were then buried in a mass grave in the pit that had been dug in vein trying to find a well.

A few days later a strange scene occurred as the Indians paraded through the white settlement with scalps hanging from their horses. The Indian women wore clothing taken from the attacked caravan.

There is an interesting epilogue to the story of the Almo Creek massacre. Eight years after the massacre, storekeeper Ames in Almo Creek is visited by a group of people that wished to see the place where their relatives had been killed. The startling thing about this event is that the visitors claimed to come from Finland!

The visitors did not stay long in Almo Creek, but hurried on towards California to look for those of their countrymen that had survived the massacre.

If this information is correct, then the biggest massacre on Whites in the history of North America would have involved a large group of Finns on their way to California in 1861!

Among historians, however, there are differing opinions as to the truthfulness of the entire story of the Almo Creek massacre. This is because the event is not documented in any other way then by oral tradition. Details about the siege had reportedly been given by an Indian, who had been one of the attackers, and later had become a friend of a white family. People that live near the alleged battle field claim to have found old weapons in the ground there, and that for long they had seen traces after a ditch the Whites had dug during the siege.

Trail usage

The following account is taken from an address of John D. Peters (1) and is referenced in the History of Box Elder County (2). It describes a conflict between emigrants and Indians which took place in Almo. This conflict is known as the Almo Massacre.

As the emigrants were camped at Durfee’s Creek, the renegade, Chief Pocatello and his band were camped only a half mile away. At nine o’clock in the morning, the emigrants broke camp and strung their cattle out ahead of them as was their usual practice. The wagons had barely pulled out of the ill-fated camp when the

Indians rushed from a small ravine, cutting the emigrants from their cattle and the herders forcing them back into a coral formation for self defense.

Behind their fortifications in the corral, the emigrants defended themselves through three nights of almost constant fighting. They had no water which must have intensified the suffering immensely. A trench was dug in which the women and children sought safety and this was probably a mistake as evidenced by tales of torture told by three members of the party who made good their escape. The Indians were numerous and had good leadership. They stayed with the fight, employing those tactics which would tell most heavily on their opponents with a minimum loss to themselves.

The three fortunate enough to escape massacre, a man and two women, made their way to Raft River. Following the stream through the Narrows, they traveled in a southeasterly direction from the head of Raft River Valley over the south pass of Black Pine Valley into Curlew Valley and eventually found their way to a herd house owned by George Reeder and George Parsons. There they were discovered and brought across the river to the home of Bishop Alvin Nichols (3) where they stayed for some time.

An estimated average of 250 wagons a day traveled the trail, with perhaps twice that during mid-summer. An estimated 45,000 traveled the route in 1850 and 50,000 in 1852. On October 7, 1849, General Persifor F. Smith, commanding the Pacific division, wrote from Vancouver to authorities in Washington about abandoning Fort Hall. If a post were established at Ft. Hall to assist emigrants, it would be nearly useless, because they follow a new route more to the southward."

Writer saw Battlefield

The writer visited this battleground in 1875. Evidence of the conflict was marked plainly by trenches thrown up under each wagon as they were arranged in circles. Accompanying our party was an old trapper who gave us a detailed account of the tragedy. In the 50 years that have elapsed the memory can cut some funny capers, and in putting this story together the writer has taken considerable pains to verify what he believes he saw and heard on the subject more than fifty years ago.

The best informer was W. M. E. Johnston, who with his wife at present lives a mile south of Twin Falls. They were 14 and 12 years of age, respectively, at the time of the massacre, and were living in the settlement of North Ogden. The impressions made on their young minds were stamped clearly.

The train & the “bits & pieces” by Arlo Lloyd

I have read from several sources about this being a well armed fairly large wagon train traveling on the Oregon Trail to California. I am not sure just how many wagons, people, horses and cattle that were in this train. We may never know. Most sources give the time as 1861 but Arlo Lloyd believes it was in 1862 and I seem to agree mostly with him because this is what his grandpa told him. This was local history and Arlo Lloyd had made a hobby of searching for these stories. He is quite a historian and has headed a few museums in Idaho.

Arlo said, “The (trains) were a cowardly bunch of ruffians”, and I agree. They thought it was fun using Indians for target practice along the way. Indian tribes began sending word ahead to tribes along the way. Soon there were three or four tribes following them. First they were scared of the Mormons and now it was Indians. A lady on the train told who ever who would listen how afraid they were. Afraid that some of the men would be recognized by the Mormons. A wagon train passing though Southern Utah a few years earlier had all been killed. This was called the “Mountain Meadows Massacre”. They also bragged about killing Mormons in Missouri and Indians in Utah, just like this party here. Arlo said, “They went way north by the way of Fort Hall to stay clear of the Mormons. Where other wagon trains began to merge with them to make a very large train. He called them, “bits and pieces”. Two sources claim it had about 300 people. Arlo said he was still unsure but it may have been a hundred or hundreds. Some like Brigham Maddsen even say it never happened but they were looking for newspaper articles and printed sources. Who would keep track or care about a bunch of emigrants this early in history.

The translation of “Ur historiens tocken” (Misty Past) from K-G Olin’s book Klippiga Bergen has made search for the massacred Finns who was part of the “bits and pieces”. Arlo Lloyd said, “It was my great grandfather who talked to the emigrating Finns about their relatives being killed after the massacre.” His grandfather’s name was Eames not Ames as in the Olin’s and other stories. “Grandfather took them to the site and to show and tell them what he believed had happened.” The Finns then went on their way to relatives in

These “bits and pieces” being completely disorganized and moving as strangers was a very dangerous thing to do. No one was in charge and neither group cared about the other. They left the main Oregon Trail and headed south to Utah on what is called the “Southern Cutoff”. Then one night they made a camp on the banks of Durfee’s Creek now called Almo Creek.

Arlo said, “The next morning the herds were gathered and driven ahead with the wagons from the original wagon train”following behind. Maybe even some “bits and pieces” went with them. But there were still some of the “bits and pieces” still circled and camped. They were now a mile away and going single file not knowing what was about to happen. They were attacked quickly killed by the Indians even though they had nothing but primitive weapons.

The still circled wagons with stood the siege for several days digging trenches for protection and even a failed attempt to dig a well. On about the fourth night two men and three women, one with a baby escaped. In the end the survivors were then tortured, mutilated and scalped. Arlo also said, “In 1885 a Colonel Chester Loveland, Territorial Controller wrote about some cowboys who were approached by a group of Indians who wanted to sell them a rope made from human hair that was taken from the victims of Almo. The cowboys not wanting it pooled their money and gave them forty dollars for it. They took it to town, prayed over it and then burnt it.

Arlo said, “Colonel Connor had heard about the massacre in California and asked to go north and take of the Indian problem. He then marched north to Idaho and attacked the Shoshone tribe at dawn. The Indians gave him quite a battle until they ran out of ammunition. The US Army rather than let them surrender massacred them all, men, women and children.

ALMO’S INDIAN LEGEND

Number 1049 August 1995

After extended grazing by California Trail oxen, cattle, horses, and mules had left a wide zone of barren range land across their domain, Pocatello’s Shoshoni band who occupied City of Rocks and other nearby valleys became alarmed. After 1860 they began to resist anymore emigrant traffic through that area. Particularly after Idaho gold rush expansion brought even more significant problems, along with devastating military campaigns, Shoshoni resentment to pressure from miners--and from extensive armed attacks--became much more intense. That unpleasant feature of Shoshoni life after 1860 led to a new dimension of tribal legends that responded to pressures from having to accommodate to farm as well as mining settlements in much of their country. A Shoshoni legend of this kind eventually gained a lot of attention from other people as well. Although its geographical setting is close to Almo and City of Rocks, it entered Idaho historical literature from North Ogden, Utah.

William Edward Johnston (who always was known as Edward) came to Utah in 1852 with his family when he was only five years old. When he grew up in North Ogden, he became a close friend of some local Shoshoni and Ute Indians. Eventually he learned both languages. He also heard fascinating accounts of clashes between Pocatello’s band and emigrant parties near Almo. In 1872, he toured Almo Valley, where he noticed traces of campground circles along with remnants of wagons and emigrant equipment. Eventually he homesteaded there in 1887, and Winecus, one of his North Ogden informants, provided him a Shoshoni legendary account of a battle to explain those Almo relics. Later still, Edward’s son, Charles Aaron Johnston, told his grandson, Charles J. Johnston (who now has a farm near Richfield) how Winecus noted that some 3,000 Shoshoni and Ute warriors assembled quietly near Almo, where they wiped out a party of some 300 emigrants from Missouri, whom they dumped into a couple of wells before they departed quietly to go on about their business. Some later reports of that affair raised emigrant losses to more than 340. Winecus’ tale has great importance, however, because it counteracts a widely accepted emigrant tendency to pass off Idaho and Nevada Shoshoni peoples as poor, incapable diggers who could not compare with emigrant capabilities for surviving battles and

thriving while passing through a desert country. Other accounts have embellished Winecus’ lore, but his version brought a distinctive Indian aspect to a kind of folklore that has characterized emigrant traditions (that go back to frontier times) of Indian hazards.

thriving while passing through a desert country. Other accounts have embellished Winecus’ lore, but his version brought a distinctive Indian aspect to a kind of folklore that has characterized emigrant traditions (that go back to frontier times) of Indian hazards.

This comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

ReplyDelete